Hollywood Cemetery’s FaceBook page recently featured this old photo courtesy of Brian Ezelle.

It looks like the 400 block of S. Cherry Street.

Hollywood Cemetery’s FaceBook page recently featured this old photo courtesy of Brian Ezelle.

It looks like the 400 block of S. Cherry Street.

From Hollywood Cemetery’s FaceBook page:

Many of the lots in Hollywood Cemetery have wrought iron fencing that is over 150 years old. With the help of talented welders, we have restored many of these fences! Here are a few Before & After shots.

From an interesting history blogpost about November 26, 1910:

At about 3p.m., John Moisant took off from the Fair Grounds in his Blériot monoplane. He circled the city, even flying over the Virginia State Penitentiary at the request of the Richmond Times-Dispatch to entertain the 1,200 inmates inside. Many other spectators gathered on Oregon Hill to watch the “Man-Bird” in action overhead.

There was recently an estate sale for The Oaks, a house in Windsor Farms…

From the sale description:

The Oaks, one of Richmond’s most historic and unique homes, was built in Amelia County around 1745. It took English craftsmen and native labor three years to construct. All of the bricks were handmade on the property. The wood was cut on the estate and allowed to season for a year before construction began. This remarkable architectural gem might not have survived to the present day had it not been for the vision and determination of Richmonder Lizzie Edmunds Boyd, who had the house moved to Richmond’s Windsor Farms in 1927 by train. Its faithfulness to the original structure is testimony to the care with which it was taken down and reconstructed. Miss Boyd was far ahead of her time as a preservationist, a community activist and philanthropist, as well as a serious collector of early furniture. While she was sponsoring Richmond’s first soup kitchen on Oregon Hill and helping found the Community Foundation, she found time to fill The Oaks with a notable collection of early American and English antiques.

It sounds like this soup kitchen may have been based in the building that appears in a Times Dispatch photograph (click here for link to RTD archives blog).

Reverend Abbott Bailey at St. Andrew’s Church was able to find out more from one of the church elders, Cyrus Field… “It was located at Maiden Lane and Belvidere Sts. This was beside St Andrews Mission, which was [the church’s] original Parish House, moved from the Baldwin Hall Location.” It was directly opposite of the house his wife Ellen grew up in.”

Neighbor Charles Pool located what he believes is the building on the 1905 Sanborn map:

This photo appeared on the Visual and Vintage Virginia FaceBook group page:

Oregon Hill historian Tom Elliott sent this moving account of the Civil War prisoner camp on

Belle Isle:

From the National Tribune, 11/10/1892

BELLE ISLE REVISITED.

A Loudoun Ranger Taken in the Spot where He Starved and Suffered.

A long cherished dream to revisit Belle Isle, the place of my imprisonment during the late war, was realized during the 26th National Encampment in Washington. We took steamers down the Potomac and Chesapeake Bay to Norfolk (next line unreadable) known in war times as the Southside Railroad. From Richmond we crossed over one arm of the James to Belle Isle on a new bridge connecting the Tredegar Iron Works with the Old Dominion Nail Works, located on the Island.

The Tredegar Iron Works is where was rolled the heavy iron plating used for the armament of the Merrimac, as well as all the heavy ordnance for the Confederacy. This important industry was then, as now, the largest in the South. The solid shot and shell used by that defunct Government was made here. Those who were so unfortunate as to be prisoners of war on he Island will probably never forget how the Confederates would test their cannon and shell made at the Tredegar Works, by firing them over the prison stockade on the Island. Quite often the shell would burst, and the fragments would create consternation among the prisoners and graybacks. I suppose everything is fair in war.

As we stepped from the bridge to the Island a panorama of 28 years ago passed rapidly before us. We looked for the stockade, but it was gone; almost all traces have disappeared. A portion of the dead-line is quite visible at the northwest corner; the paraphet that was once about 13 inches high.

A map the writer made of the prison-pen some 10 years ago, exclusively from memory, was produced, and was as accurate as if made by a civil engineer, on the ground. We have always insisted the prison, after it was enlarged in the Fall of 1863, contained about two acres of ground. Now I know I was accurate in that statement. Where the prison-pen was located is now an immense rolling-mill owned and operated by the Old Dominion Nail and Iron Co. Where the writer lay in the sand with P. A. Davis and Rube Stypes, and where both died during that memorable Winter of 1863-’64, is now located a large Fairbanks scale for weighing ore.

Where the prisoners caught Serg’t Haight’s dog, and ate him in about 15 minutes, is now a large set of rolls, rolling out red-hot bar-iron. Where the hospital tent was located, beside which the dead were piled up to the number of 200 waiting burial, is now an immense bank of dead cinders from the rolling mills.

I walked down to the dead-line, where poor Jeff McCutchen was shot for getting too near that line. I picked a sprig of the National flower, the golden-rod, from as near the exact spot as I could locate it. I stepped upon the parapet, now not over 18 inches high, where the two little boys who belonged to the 13th Regulars would get with fife and drum and sound the grub call. What sweet music it was to the starving prisoners!

I walked to where the gate was located that led to the river for water and the sinks where we traded our last gutta-percha ring for a half dozen biscuits. At the same place I also traded the copy of the New Testament that was sent to me by the Christian Commission, in return getting one dozen biscuits. The physical man was perishing then, and not the spiritual. I walked up to the hill where was located the cannon that pointed its ugly nose down on the prisoners. The guards took especial delight in telling us they captured this gun at Bull Run. As I walked back towards the once stockade I met a green snake coming towards me. I did not argue the point, but began pounding Mr. Snake with my walking stick.

I was eager to conquer this enemy on the island, and as upon my first visit the serpent had me, but now the table was turned, and I thought of the many thousands of our fellow prisoners who had suffered here, and then I pounded Mr. Snake again. While Mr. Snake was probably not to blame for my mistreatment on the first visit, yet I readily seized upon the pretext of holding him responsible, and beat him until he was dead, dead, dead.

I walked down to the gate where 100 men were taken out every morning for Andersonville. I had always tried to get out before my turn, but was always detected; when Serg’t Haight would bring down his long club on my head, and send me back to starve awhile longer.

Mr. Baird, who was born on the Island, now the Superintendent of the Old Dominion Nail Works, was exceedingly kind and pleasant to me. He showed the large kettle that was used to boil the morning bean soup for the prisoners. It is now used to mix cement in to lay firebrick. This relic the National Prison Association should possess. I believe the Old Dominion Works would present it to that association gratis. Mr. Baird also showed us about 10 or 12 tons of the iron plate that formed the armament of the Merrimac. He had bought it for old iron. Several pieces showed dents in them three or four inches deep made by the solid shot from Ericsson’s Monitor. He has had several kegs of nails made from the same material, and took great pleasure in presenting our party with two each. We were also shown one wing of the nail works that was built by the prisoners, as good as the day it was put up, a splendid job of masonry. All prisoners (bricklayers) that worked on the building got double rations of corn-dodger, and glad to get the job.

Most of the prisoners who died on the Island (starved to death) are now buried in the National Cemetery about three miles east of the city; over 5,000 are unknown. This was the result of carelessness on the part of the Confederates. When a prisoner would die we would always give his name, company, and regiment to the Confederates, who would write it out on a piece of paper and pin or stick it in a buttonhole, or lay it on the body, but when as many as 200 at a time would lay out in the rain and snow for two weeks, before burial, nearly all the names would be blown away or lost. Hence so many unknown. Those that sleep there now the flag for which they died waves proudly over them.

“Rest on, embalmed and sainted dead,

Dear as the blood ye gave;

No impious footsteps here shall tread

The herbage of your grave,

Nor shall your glory be forgot,

While fame her record keeps,

Or honor points the hallowed spot

Where valor proudly sleeps.”

Our party each cut a sycamore cane from the sprouts that have grown up in the stockade, and walked off the Island with none to molest or make us afraid. – BRISCOE GOODHEART, Loudoun (Va.) Rangers, Knoxville, Tenn.

Was in Squad No. 34 on the Island.

From the TimesDispatch.com:

This January 1953 image shows houses on Belvidere Street in Richmond, as seen near Rowe Street, which were to be taken by the city for a proposed war memorial. The row formed the western boundary of a block that city officials were preparing to acquire. The Virginia War Memorial was dedicated in February 1956.

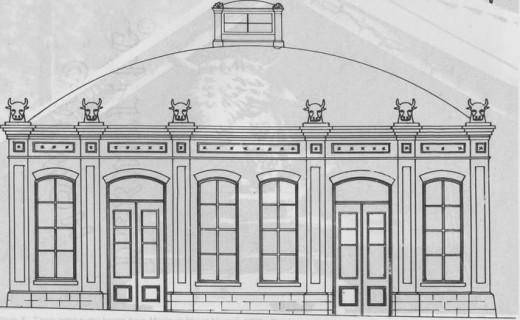

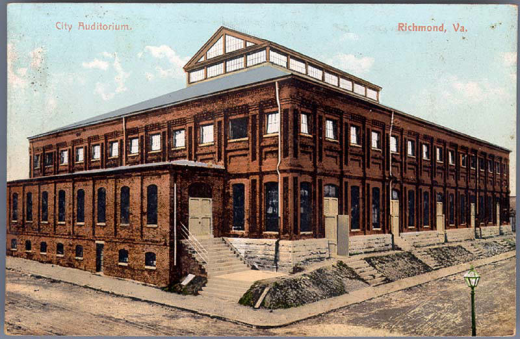

The Shockoe Examiner blog has a recent, interesting post on the long gone 1886 Marshall Street Meat Market that compares other buildings, including the VCU Cary Street Gym (the 1892 Clay Ward Market, old City Auditorium), and D.C.’s National Building Museum (the 1887 Pension Building).

(Original architectural drawing of Cutshaw’s design for the Marshall Street Meat Market, from the collection of the Library of Virginia.)

(Postcard image of what was then called the City Auditorium, ca. 1910. Now VCU Cary St. Student Recreational Gym)

From Valentine Richmond History Center website:

October 25, 2014

Explore the significant role that women’s groups played in Hollywood Cemetery’s history from the Civil War to the present. Stops include gravesites of female residents who led independent lives as educators, authors, preservationists, suffragists, humanitarians or as the power behind the scenes of famous men.

$15 per person

$10 for History Center Members

Walk-ups welcome.

Cash or check, or purchase online.

On-street parking.This tour is presented as part of the Richmond History Tours program, a service of the Valentine Richmond History Center.

From Hollywood Cemetery’s FaceBook page:

If you haven’t had a chance to read “Winnie Davis: Daughter of the Lost Cause”, you can buy a copy of the book at our event on Oct. 8th. Author Heath Lee will be talking about the book’s connections to Hollywood Cemetery and signing copies. We hope you’ll attend!